Understanding how sleep-disordered breathing can impact dental health can be critical to the long-term success of restorative treatment. In this case report, the patient had a large diastema that was successfully closed with porcelain veneers, which caused unexpected, unesthetic complications several years later. This case demonstrates that if clinical attention is focused solely on restorative techniques or clinical management of patients, without considering potential airway issues, unexpected restorative complications may arise in the future. Learning and understanding the origins of the signs and symptoms of sleep-disordered breathing can be critical to preventing future problems and optimizing the patient's overall health.

Few articles provide long-term clinical outcomes, but it is important to see such outcomes to be able to fully appreciate the prognostic value of restorative dental treatment. Following patients, assessing their current dental health, and providing restorative treatment should be done over time, as this can help clinicians understand the etiology of adverse outcomes and influence decisions about dental treatment plans and their long-term predictability. This article discusses the implemented treatment plan, the step-by-step clinical process, and the follow-ups performed 3 and 14 years later, where over-eruption of all maxillary central and lateral incisors caused increased esthetic risk due to coronal and uneven tooth movement. In this case, exposed margins of the restorations may have developed due to potential airway issues.

Case Overview

Initially, the patient was unhappy with the significant diastema between the maxillary central incisors (Photos 1 and 2). The patient considered maxillary veneers as a solution to the problem. After a thorough examination of the dentition, soft tissues, and jaw relationships, some minor esthetic issues were noted in the dentition as well as functional issues with the current dental arrangement related to resolving the patient's primary concern, namely: the existing diastema between the maxillary central incisors was too large to be closed with the patient's current dental arrangement. In addition, the wear pattern of the patient's anterior teeth indicated either a limited chewing amplitude or a frictional chewing pattern (Photo 3). Therefore, pre-prosthetic orthodontic treatment was recommended as a conservative approach to address both the patient's esthetic and functional concerns. However, the patient chose to forgo the recommended orthodontic treatment at that time.

Photo 1: Patient's smile, frontal view, before treatment. Please note the large diastema between teeth 1.1 and 2.1.

Photo 2: Photo of a full-face smile before treatment.

Photo 3: Before treatment, the patient is in a state of maximum tuberculo-fissure contact, indicating wear corresponding to frictional chewing or limited chewing amplitude.

Two years later, the patient returned with a review of the recommendations from the previous treatment plan. After updating the collected data and fully assessing the patient's current condition, the treatment recommendations were discussed again with the patient. In addition to the large diastema, the patient had bimaxillary retrusion. This time, the patient accepted the proposed treatment plan. His medical history was not supported by any evidence, although he reported a history of smoking. The patient acknowledged wearing surfaces on several posterior teeth, several sensitive teeth, and a chronic teeth grinding habit.

Risk Assessment

Periodontal: Stage I, Grade B. Risk was moderate due to smoking; prognosis was favorable (Photo 4). Biomechanical: Risk was low; prognosis was favorable. Functional: Risk was moderate due to difficulty chewing or abrasion; prognosis was favorable to unfavorable. Dentofacial: Risk was low due to poor labial dynamics; prognosis was unfavorable due to large central maxillary diastema and patient’s decision to forgo orthodontic intervention.

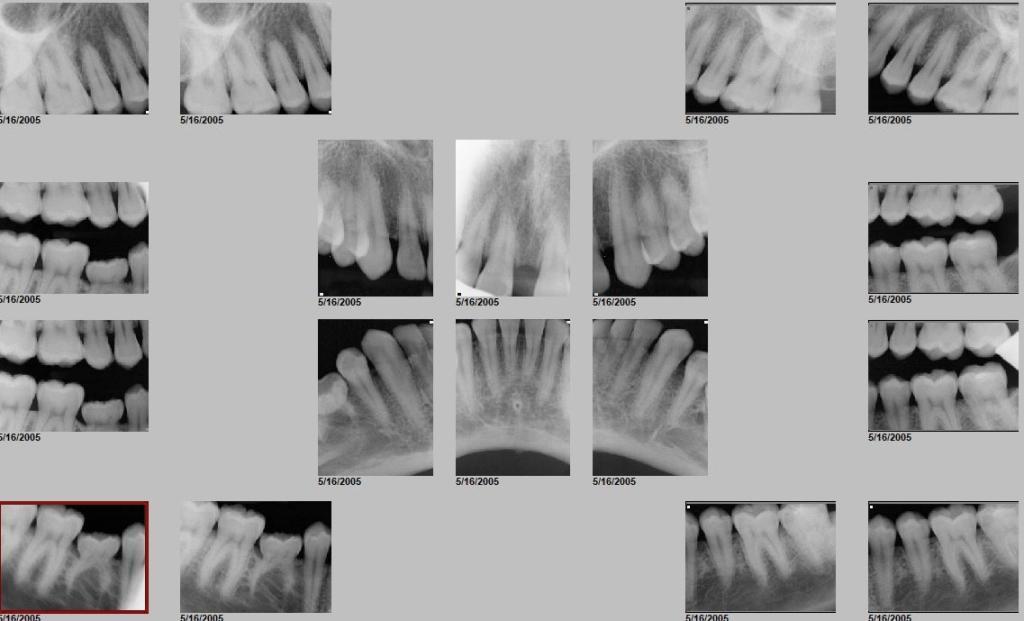

Photo 4: Pre-treatment full-mouth radiograph.

Examination of the soft tissues revealed prominent high frenulums of the lips and cheeks, both upper and lower jaws, as well as a high frenulum of the tongue. The patient also spoke with moderate sigmatism.

Sequence of Treatment Plan Implementation

The first phase of treatment involved performing a complete, comprehensive orthodontic treatment to correct functional issues and improve tooth alignment, thereby predictably addressing esthetic concerns. Treatment phases included improving the curve of Spee by aligning the upper and lower occlusal planes and removing the intruding teeth 1.5 and 1.4, which were likely over-erupted due to the ankylosed primary tooth 8.5, and properly distributing the spacing between teeth 1.3-2.3 to close the diastema with minimal tooth preparation for post-orthodontic restorations. The ultimate goal was to establish a minimum horizontal and vertical overlap of at least 1 mm to provide horizontal space for occlusal plane alignment if needed. This treatment plan reduced functional risk and promoted a predictable outcome of bilateral, equal-intensity, simultaneous occlusal contact of the posterior teeth.

The second stage of treatment involved the preparation, fabrication and placement of four maxillary porcelain veneers for teeth 12 to 22 and a CAD/CAM fabricated continuous crown (CEREC, Dentsply Sirona) on tooth 85. Before restoring teeth 12 to 22 with porcelain veneers, a facebow and bite registration was performed and a diagnostic model was ordered on a fixed platform (Figure 5). The platform allowed the dental technician to properly space the teeth and plan future restorations. Despite significant advanced planning, a small diastema must be maintained to maintain the proper size and spacing of the restorations. The preparation of teeth 12 to 22 for the feldspathic porcelain veneers was minimally invasive (Figure 6) and a polyvinyl sulfate impression was taken. After checking the margins, esthetics and functionality, the prepared teeth were etched with 35% phosphoric acid and an adhesive (OptiBond SoloPlus, Kerr) was applied. The veneers were then bonded with a light-curing resin material (RelyX Veneer Cement, 3M Oral Care) (Figure 7) using glycerin gel to prevent the formation of any oxygen-impeding layers at the margins. At the same appointment, tooth 8.5 was completely prepared and a crown (CEREC) was fabricated and cemented with a self-adhesive resin cement (RelyX Unicem, 3M Oral Care).

Photo 5: Diagnostic model.

Photo 6: Minimally Invasive Porcelain Veneers on Teeth 1.2 to 2.2.

Photo 7: Porcelain veneers on teeth 1.2 to 2.2 after treatment. Note the facial levels of the upper and lower jaws in relation to the canines (as indicated by the black horizontal lines).

In the third stage of treatment, a Hawley maxillary acrylic palatal retainer was fabricated and installed, while the mandibular anterior teeth were stabilized with fixed wire from 3.3 to 4.3. The patient strictly followed the recommendations for daily wear of the maxillary retainer after childbirth.

Problems appear after 3 years

At a routine preventive appointment 3 years later, during a clinical examination, fluctuation and mobility of the central and lateral incisors of the upper and lower jaws were noted. The occlusion, which was successfully treated 3 years ago, changed and its previous function returned.

A Kois maxillofacial deprogrammer (Kois Center) was fabricated and delivered. A follow-up visit confirmed the differential diagnosis of limited range of motion (LOM) because the first contact in centric relation (CR) was at the anterior incisors. CR could be used as a reference because the patient was negatively loaded and there were no joint sounds or pain during the immobilization test. To help establish a stable, functional occlusion, a Kois deprogrammer was used to design orthodontic treatment and properly manage the LOM. Orthodontic brackets were placed on the mandibular arch to move teeth 3.2 through 4.2 lingually (Figure 8) and eliminate any premature CR contacts between the anterior incisors (Figure 9). The patient was fitted with a maxillary Hawley retainer and a mandibular Inman retainer.

Photo 8: Installed Kois deprogrammer and mandibular orthodontic braces at a 3-year follow-up.

Photo 9: 6 o'clock superior view; inverted inferior frontal view after orthodontic treatment Note that the patient's sagittal gap is 1 to 2 mm.

Patient Returns After 11 Years of Absence

Throughout the treatment, the patient was highly cooperative and disciplined. However, after treatment, he and his family moved out of state and no longer visited the clinic. They were not heard from for 11 years until the patient's spouse contacted the clinic, stating that the patient planned to return for replacement veneers. His main concern now was the exposed, stained edges of the veneers.

The patient was asked to complete current medical and dental questionnaires, as well as the Lamberg Sleep Questionnaire (LSQ), which is designed to determine the correlation between sleep quality and health status. In addition, current intraoral photographs and a panoramic X-ray were requested and obtained from the patient's dentist in his new hometown.

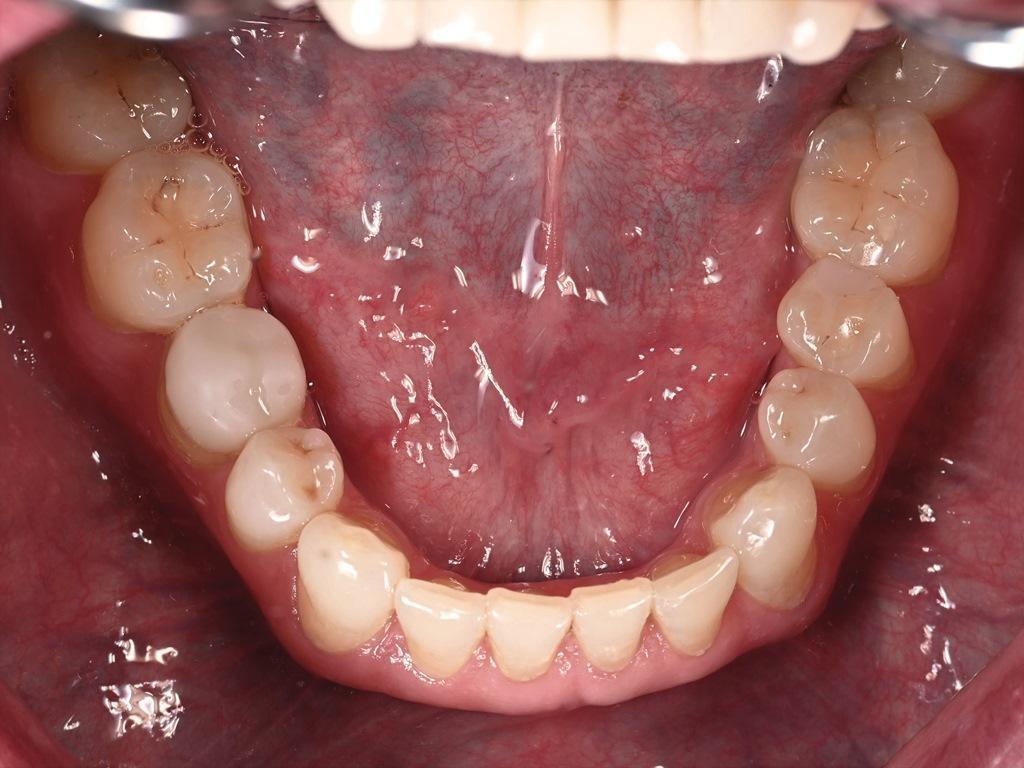

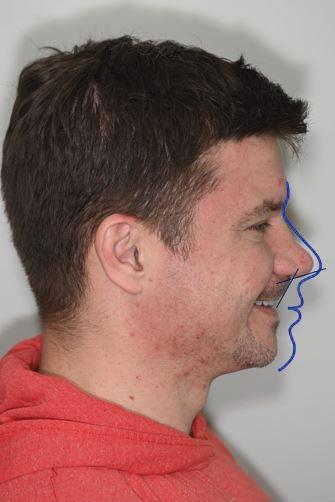

Recent intraoral photographs of the patient revealed no structural defects in the porcelain veneers (Figure 10). There were no abraded incisal edges or surfaces on either the maxillary veneers or the unrestored mandibular anterior teeth (Figure 11). All maxillary incisors were over-erupted, especially #21, and the free gingival margins of the maxillary central and lateral incisors had migrated coronally (Figure 12). Radiographically, there was no evidence of bone loss or increased pocket depth (Figure 13). The patient's profile showed unchanged maxillary and mandibular retrusion (Figure 14). Coronal migration of the gingival margins of the mandibular incisors was also noted, as was a significant midline labial frenulum.

Photo 10: View of the occlusal surface of the maxillary teeth 14 years after treatment. Note the intact porcelain veneers on teeth 1.2 through 2.2.

Photo 11: View of the occlusal surface of the lower teeth 14 years after treatment. Note the absence of abrasion on the intact incisal edges of the anterior teeth.

Photo 12: Gingival levels 14 years after treatment. Note the excessive eruption of teeth 1.2 to 2.2 (especially 2.1) and 3.2 to 4.2 (as shown by the black horizontal lines).

Photo 13: Panoramic radiograph 14 years after treatment. Note the absence of radiographic bone loss.

Photo 14: Profile of a patient with bimaxillary retrusion.

Risk assessment: 14 years later

Fourteen years after the initial risk assessment, the patient's risk assessment was as follows.

Periodontal: Stage I, Grade B. The risk was low because both the risk and status remained unchanged. Biomechanical: The risk was low and remained unchanged. Functional: The risk was moderate (presumably due to positive answers to the dental history questions: the position of the anterior teeth had changed, the bite had changed, he clamped his tongue between his teeth, bit his nails, and wore retainers. After treatment, the patient's dental function was satisfactory.) Dentofacial: The risk was low and remained unchanged (due to low lip dynamics); however, the prognosis was now worse because the margins of the teeth were exposed, as the teeth moved unevenly, more toward the incisors.

The patient's medical history had changed significantly from his previous medical history 14 years earlier. The patient now reported taking the hormone testosterone and suffering from frequent sinus congestion. In addition, on the LSQ screening questionnaire, he frequently reported feeling tired, tingling in the arms, muscle weakness, irritability in the morning, and decreased sexual desire. These complaints were literature-supported signs and symptoms associated with respiratory problems, such as breathing and sleep disturbances.

“Red flags” were present

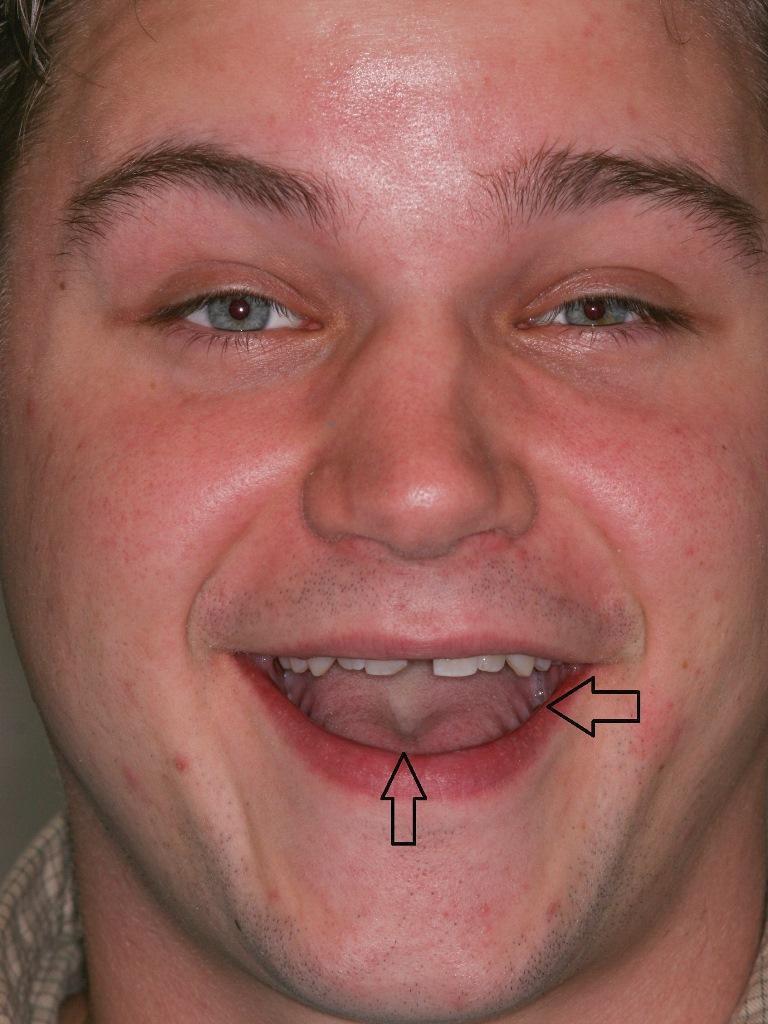

In retrospect, the patient had had multiple clinical warning signs of airway problems in the 14 years prior, including taut soft tissues under the tongue and a significant labial frenulum (Figure 15), which could negatively impact the alignment of the teeth. Also noticeable were a scalloped tongue and a midtongue dimple (Figure 16); a prominent midtongue dimple on the dorsum of the tongue is often indicative of tongue tie. His history and recent photographs revealed that he had bimaxillary retrusion, which is a common risk factor for patients with sleep-disordered breathing.

Figure 15: A significant upper labial frenulum is visible in the midline.

Photo 16: Photo of the face before treatment. Note the protrusion of the tongue (arrow on the right) and the dimple in the middle of the tongue (arrow on the bottom).

Common and frequent causes of dental restorative treatment failure are often found in the periodontal, biomechanical or functional areas. Notably, the patient's current dental history indicated that his teeth had shifted in position over the past 5 years and he frequently stuck his tongue between his teeth. Clinically, the cervical margins had shifted and the teeth were over-erupted. Although the cervical margins may have been exposed by toothbrushing, this does not explain the tooth displacement and change in position. The actual cause was much more complex and multifactorial.

A recently presented clinical scenario 14 years after successful treatment and the need to define a new predictable treatment plan raise important questions: What caused the teeth to shift and not to shift uniformly? How predictable would it have been to expect a different long-term outcome if the patient had been treated in a similar manner? What was the etiology of this failure and can it be found in the dental or medical literature? Were there clinical signs and symptoms or clues in the patient's history, questionnaire or data collection? Could dental changes such as over-eruption, malposition, wear or erosion be signs associated with a health risk rather than an isolated problem? Could the soft tissue, tongue, buccal and labial frenulum have been a marker for an unfavorable outcome even several years earlier? Were structural features of the patient's anatomy, evident in his profile photographs, “red flags”?Positive patient responses to the LSQ questionnaire indicate sleep-disordered breathing and should raise suspicion for potential respiratory, sleep and soft tissue dysfunction, the latter of which includes proven causes of instability after orthodontic treatment (e.g. tissue rupture, mouth breathing, reverse swallowing, etc.). If such dysfunction is diagnosed and corrected or at least ameliorated before restorative treatment, the long-term outcome and stability will be significantly improved. As for occlusal changes, since there is no evidence in the literature of the innate ability of teeth to move independently after the eruption stage, the cause is the constant loads, be they light or heavy, which must come from the muscles; therefore, stabilization of the soft tissues is necessary.

This case illustrates the potential complications that can arise from unrecognized signs of airway problems in the patient. If left untreated, such problems can significantly negatively affect the long-term success of restorative dental treatment and the general health of the patient. He also emphasizes the importance of proper examination and discussion with patients about their risks, both from a dental and medical perspective.

To paraphrase Machiavelli, the 16th-century Italian statesman, diplomat, and philosopher: “…because at first the diagnosis is difficult and the cure is easy. Later the diagnosis becomes easy, but the cure is difficult and sometimes impossible.”

By Bozidar L. Kuljic, DDS