Plasma cell gingivitis (PCG) is a rare benign disease that typically affects the marginal and adjacent gingiva. This case report describes generalized PCG in detail, including patient management and the clinicopathological characteristics of the disease.

Plasma cell gingivitis (PCG) is an extremely rare reactive inflammatory disease of the gums with an unclear etiology. Its incidence and prevalence are controversial, as only a few cases have been reported in the literature. PCG typically affects the anterior maxillary gingiva, but may involve any marginal and/or attached gingival tissues, and in some cases may involve the tongue and other oral friable tissues. The clinical presentation of PCG is often described as gingival redness with distinct histologic evidence of intense inflammatory cell infiltration. If it is generalized PCG, the cause is usually not limited to a single source, and the plasma cell response is usually massive.

Kerr et al first described PCG as “allergic gingivostomatitis” and attributed it to a contact hypersensitivity reaction to chewing gum and/or hard candy. Other authors have also cited possible allergens such as peppermint, cinnamon, herbal products, dentifrices, and spices/flavors as a cause. One review even suggested that plaque bacteria may be involved. Silverman and Lozada suggested that fungal overgrowth may play a role in the etiology. There has even been skepticism as to whether PCG should be considered a distinct clinical entity at all, distinct from plaque-associated gingivitis and periodontitis.

Clinically, PCG presents as a well-defined, erythematous and edematous lesion involving keratinized tissues but not the adjacent mucosa. The gingiva, which is usually not ulcerated, appears smooth and almost glossy, and may also appear friable and tender in some patients. The gingival tissues may bleed even with mild, unintentional irritation, leading some patients to believe that it is spontaneous. A recent report documents a case of PCG that was initially thought to be an aggressive plaque-associated periodontal disease. Given that the clinical picture may mimic other neoplastic diseases, including monoclonal plasma cell-associated lesions, early workup, complete differential diagnosis, and biopsy with appropriate histologic evaluation are essential.

Treatment of PCG involves treating symptoms while simultaneously evaluating for a potential causative agent that may be responsible for the disorder. Elimination therapy and dietary review may help identify the causative agent. Most patients respond to therapy, although relapses are not uncommon; progression to malignancy has not been reported.

This report of successful treatment of a patient with PCG documents the successful management of a patient with PCG and provides a review of the relevant literature.

Case Report

In 2020, a 24-year-old African American female was referred to the periodontal clinic at Augusta University College of Dentistry, Augusta, Georgia, with a chief complaint of “gums that are bleeding, very red, and painful.” Significant factors included a history of sickle cell disease and systemic lupus erythematosus. The dental history was unremarkable except for 18 months of orthodontic treatment that had been completed 5 years prior to the current presentation.

The patient reported using a desensitizing toothpaste daily along with an antimicrobial mouth rinse (essential oil based). Oral examination revealed diffuse erythema and generalized swelling of the gingivae over the facial keratinized tissues of the maxilla and mandible (Figure 1). The tissue was friable and bled easily on palpation and tooth brushing. Probing depths were generally 2mm to 3mm with profuse bleeding on probing of the lesions. There was no evidence of attachment loss, mobility, or furcation throughout the dentition.

Figure 1: Initial presentation.

Clinical case management

Before clinical intervention, differential diagnosis between PCG, cicatricial pemphigoid and lichen planus was performed during consultation with an oral pathologist. Cicatricial pemphigoid or mucous membrane pemphigoid was considered as it usually presents with painful blisters on the oral mucosa and areas of desquamative gingivitis. Similarly, oral lichen planus affects the gums causing redness, swelling, scaling or blistering. The appearance of oral lichen planus could also be due to allergy, which was the suspected etiology in the initial examination. The histological appearance of lichen planus is characterized by characteristic features such as epithelial hyperplasia resulting in a sawtooth pattern with wedge-shaped hypergranulosis. On the other hand, cicatricial pemphigoid is confirmed by histological examinations and direct immunofluorescence. Histologic features include subepithelial blisters with mixed inflammatory cell infiltration.

Under local anesthesia with 2% lidocaine with 1:50,000 epinephrine and 4% articaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine, a needle biopsy of the vestibule of the oral cavity in the left maxillary region was performed to a depth of 3 to 4 mm above the attached gingiva. The patient was prescribed dexamethasone mouth rinse (0.5 mg/5 ml) and advised to discontinue her mouth rinses, dentifrices and oral contraceptives as a preventive measure. She was also referred to her general practitioner for a complete blood count to identify any potential allergens that could be causing the condition and, on the advice of the physician, a patch test was performed.

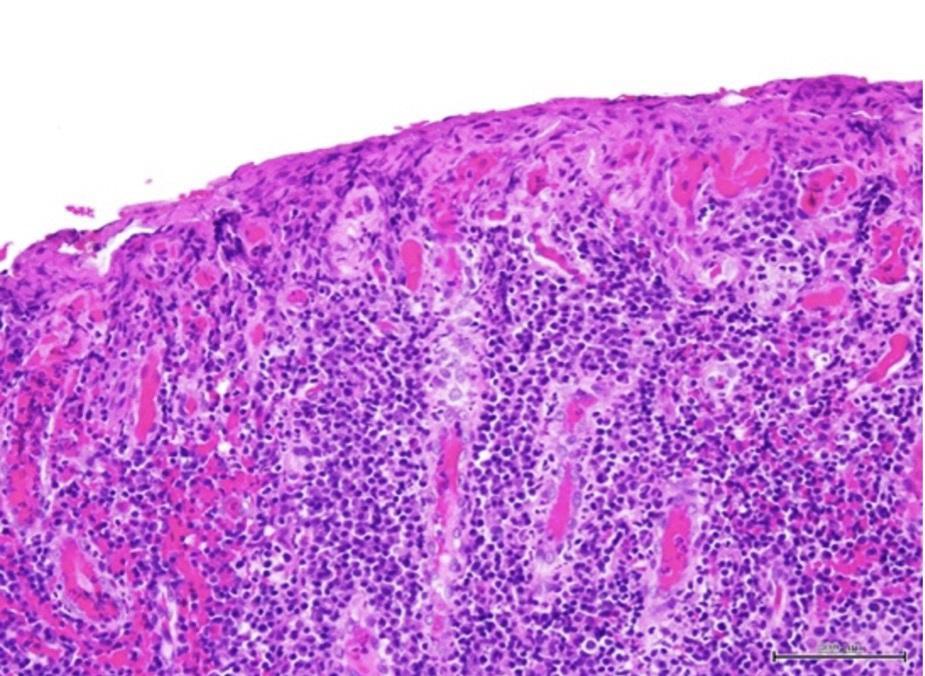

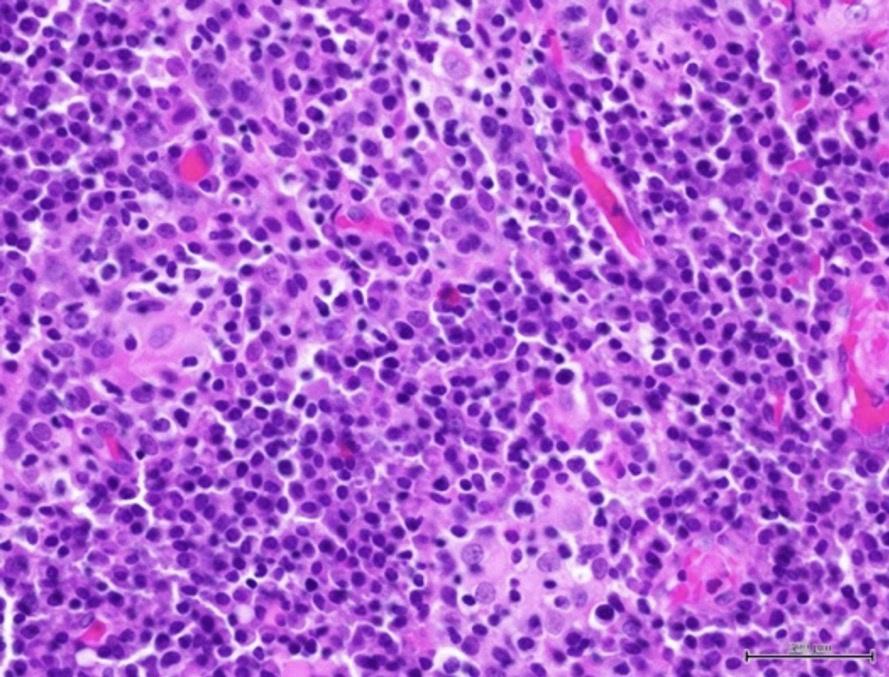

Histological examination of the attached gingiva specimen revealed erosion of the superficial epithelium and the presence of a dense inflammatory cellular infiltrate consisting predominantly of plasma cells (Figure 2). The specimen was coated with fibrinous deposits and contained superficial dilated blood vessels filled with red blood cells with occasional vertical streaks of residual epithelial cells with uniform basophilic nuclei surrounded by variable amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm. The lamina propria with an ill-defined basal layer supported a dense inflammatory cellular infiltrate consisting mainly of densely packed plates of plasma cells with their characteristic eccentric basophilic nuclei with wheel-like chromatin surrounded by eosinophilic cytoplasm with clear perinuclear zones (Figure 3). A specimen obtained from the left maxillary gingiva showed severe chronic mucositis with predominant plasma cell infiltrate, epithelial erosion, and stromal eosinophilia, consistent with PCG. The presence of stromal eosinophils is consistent with allergic gingival inflammation. No evidence of neoplasia or granulomatosis was found in any of the specimens. The clinical presentation and histopathological features led the authors to conclude that PCG was the diagnosis.

Photo 2: Histopathological examination of dense inflammatory infiltrate under low magnification (x100).

Photo 3: Histopathological examination of concentrated plasma cells under high magnification (x400).

In this clinical case, the only treatment was dexamethasone. No allergens were identified.

Clinical outcome

The patient was followed up 4 weeks after the initial presentation and reported improvement in symptoms since that presentation (Figure 4). Two years after the initial presentation, the patient showed improvement in clinical signs and symptoms in the previously affected areas (Figure 5). The gingival inflammation and swelling were markedly reduced and areas of keratinization were appearing. At this final follow-up examination after 2 years, the patient had a very favorable clinical outcome. The gingiva appeared generally healthy with no visible swelling or attachment disturbance. Complete clinical cure of PCG was reported with no adverse symptoms.

Figure 4: Four weeks after initiation of therapy.

Photo 5: The final condition of the patient 2 years after the start of treatment.

Discussion

Plasma cell gingivitis is a rare benign inflammatory disease characterized by polyclonal proliferation of plasma cells distributed at the mucogingival junction. This disease is also called atypical, allergic, or idiopathic gingivostomatitis and plasmacytosis.

It is generally considered to be a hypersensitivity reaction to certain antigens contained in chewing gums, toothpastes, and hard candies, but its etiology is still unclear. Kerr et al. in 1971 reported a case of PCG resulting from an allergic reaction to cinnamon, which was added to chewing gums as a flavoring agent. Inflammatory reactions were observed in both attached and free gingiva due to flavoring agents added to toothpastes and chewing gums. The pathogenesis of the disease may be the result of chronic inflammatory changes leading to local immunologic dysregulation, causing plasma cell migration with the help of proinflammatory cytokines. This mechanism triggers B cell proliferation, which ultimately leads to the clinical manifestations of PCG.

PCH has a variable clinical presentation but presents as painful, edematous, and erythematous lesions that bleed easily, with or without ulceration. Histologic examination typically reveals dense plasma cell infiltration into the subepithelial connective tissue, a feature also seen in neoplasms, autoimmune vesicobullous diseases, and lymphoproliferative disorders. Therefore, differential diagnosis of this condition is critical to exclude outliers.

Because of the unknown etiology of the disease, therapy is often aimed at relieving symptoms and identifying and eliminating triggers. First-line treatment includes corticosteroids, immunomodulators, antibiotics, and antiplaque mouthwashes.

Conclusion

This case report presented an atypical inflammatory gingival disease: plasma cell gingivitis. This condition is generally thought to be caused by an allergic hypersensitivity reaction, but the exact etiology is still unclear. Identification of the causative antigen may take time and may delay treatment/recovery. Successful treatment of this condition requires careful evaluation, treatment, and histologic examination of the lesions. In this case, biopsy results confirmed the diagnosis of PCG, and signs and symptoms resolved within 1 month. Treatment included dexamethasone mouth rinses and avoidance of potential allergens. Approximately 2 years after initial diagnosis, the patient is clinically stable.

Authors:

Celine Joyce Cornelius Timothius, BDS, MSc, MS

Ilanit Stern, DDS, MS

J. Kobi Stern, DDS, MS

Rafik A. Abdelsayed, DDS, MS

Mark E. Peacock, DMD, MS